Worldwide Sites

You have been detected as being from . Where applicable, you can see country-specific product information, offers, and pricing.

Keyboard ALT + g to toggle grid overlay

Bringing water and power to the west

The US Congress established the Bureau of Reclamation in 1902 with the objective to “reclaim” arid lands for human use through irrigation. The agency now maintains 492 dams in 17 western states and delivers 10 trillion gallons of water to more than 31 million people each year. It’s the second-largest producer of renewable hydropower in the nation, generating 40 billion kilowatt hours of electricity annually.

Today, more than a century after its founding, the agency’s mission is evolving. In addition to sustaining the communities of the western United States, its goal is to reclaim its own assets from the ravages of time. “These facilities are so important to the nation,” says David Winslow, CAD manager and civil engineer at the Bureau of Reclamation in Salt Lake City, Utah. “And we’re tasked with managing something that’s going to be around for hundreds of years into the future. After we’re long gone these structures will still be there. But they have to be operated and maintained properly.”

Infrastructure maintenance: a global challenge

Glen Canyon Dam was completed in 1963, amid a worldwide boom in dam-building that took place from the 1950s to the 1970s. About a thousand dams a year were completed during that period—including Aswan High Dam on Egypt’s Nile River, Kurobe Dam in Japan, Idukki Dam in India, Ilha Solteira Dam in Brazil, and Contra Dam in Switzerland—to bring electricity, water, and flood control to regions around the globe.

In that era, there was no CAD to help create these massive infrastructure projects. Glen Canyon, one of the largest concrete dams in the world, “was built with slide rules and trigonometric tables,” Winslow says. “All the drawings were created by hand on drafting tables.” With only paper plans and blueprints to rely on, Reclamation has had limited insight into the effects of aging, weather, and extreme changes in water flow on the dam’s condition.

This problem isn’t unique to Glen Canyon: Of the more than 58,000 large dams in the world, over half of them have been in operation for at least 50 years, according to the World Bank. The need to find better tools for dam maintenance and resilience is clearly a global challenge.

New technology tools to diagnose an aging dam

Reclamation consulted with Autodesk to select the best tools and techniques to create a detailed 3D digital model of the structure: a “virtual” Glen Canyon Dam. Three-dimensional data offers depth and context beyond what the bureau’s 2D paper documents can provide. And digital data is dynamic: It’s not frozen in time like an old blueprint. Digital models can be updated, new scenarios can be simulated, and changes can be measured against the original data set for centuries to come.

A 3D model would provide Reclamation with an enormous new set of capabilities to help manage and maintain Glen Canyon Dam. It would make it easier to find, diagnose, and repair current damage—and predict and prevent future damage.

But how do you create a computer model for a structure built before CAD? The answer is reality capture.

Capturing massive data from a massive site

Reality capture involves collecting data about an object—visuals and measurements of size, shape, and position—and compiling it into a computer model. Reclamation, using funding from its Science and Technology program, contracted with Autodesk to collect the required data and produce 3D models while Reclamation employees observed the procedures and processes. In August 2016, Reclamation and Autodesk began capturing data for the dam, using laser-based scanners (known as lidar), sonar, and cameras to document the site.

The Autodesk team scanned and photographed the dam and its surroundings, a huge undertaking that took a full week of 12-hour days. Team members captured images and measurements of the interior and exterior of the hydropower plant, the downstream and upstream faces of the dam, the crest of the dam, the surrounding landscape, and even part of the visitors’ center. They collected 700 lidar scans and thousands of photographs and video, captured from the land, water, and air using an arsenal of advanced tools.

Transforming data into digital models

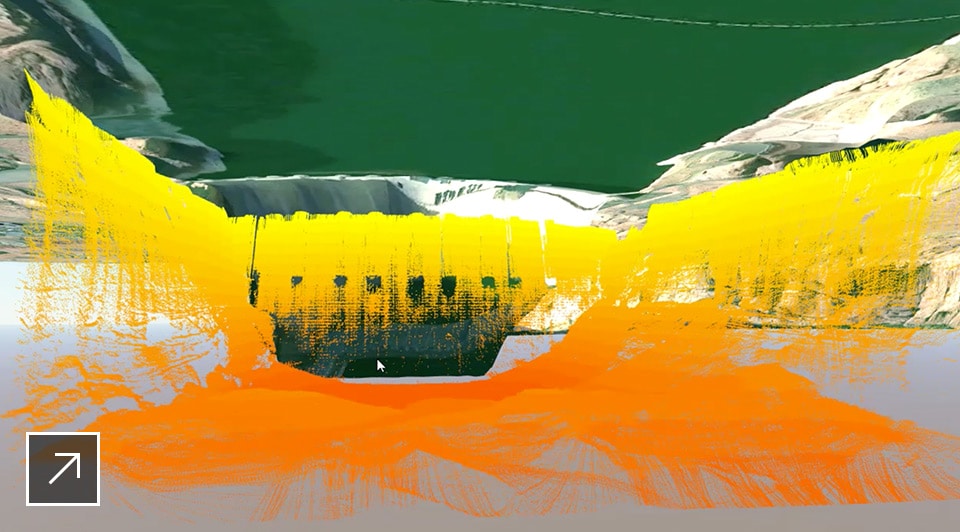

The scans of Glen Canyon captured stunning visuals and millions of data points in rich, photorealistic 3D point clouds. Photo models were created from the team’s photographs by merging overlapping pictures in a process called photogrammetry. To bring all this raw data together, the team used ReCap Pro to compile a larger, more comprehensive point cloud.

After importing the point cloud into Revit, the team built a 3D technical model that was filled in with the individual components of the dam, from the structural steel to the hydroelectric generators. This model combines old and new, mapping together the old 2D drawings with the advanced point cloud data, so users can comprehend not only the dam’s pieces and parts, but how they fit together as systems.

In the final phase of the project, the team will import the technical model into InfraWorks and add real-time data streams about the dam’s performance—how much water is being released, for example, and how much electricity is being generated. The result will be a dynamic virtual representation of the dam to help operators identify risks that must be addressed and opportunities that can be exploited.

Forecasting the future

Reclamation will use its dynamic 3D model of Glen Canyon Dam as a tool for operators and employees of all skill levels. “This will be a multi-use model,” Winslow says. It also offers new ways to educate the public: for example, by sharing video walkthroughs of the virtual dam, particularly in areas where visitors can’t go safely. The agency plans to create similar 3D models for its other assets, possibly including Nevada’s Hoover Dam and Washington’s Grand Coulee Dam.

Most importantly, the model is a critical tool to prepare for the uncertainties that lie ahead. “Year to year, water flow and weather are variable, and we don’t know exactly what we’re going to get in terms of inflow to the reservoir,” Winslow says. “We’re trying to understand how we can best supply water for the future of the nation—not only for the rest of this century, but past that.” The dynamic 3D model is, he continues, “a tool that can be used by many different disciplines to help us to better manage the facility as we go through the years.”

Technology tools with global impact

Today, dam operators all around the globe need to prepare for an uncertain future. Initiatives are underway to rehabilitate dams of similar vintage to Glen Canyon. Among them are Africa’s Kariba Dam, completed in 1959; California’s Oroville Dam, completed in 1968; and Australia’s Burdekin Falls Dam, completed in 1987; along with national programs to upgrade dams in Indonesia, India, Armenia, and Vietnam. The 3D model creation process pioneered at Glen Canyon Dam, Winslow says, “can help dam owners and operators throughout the world do a better job of operating and managing their facilities for the future.”

At Glen Canyon and other aging dams—not to mention aging power plants, bridges, ports, and other pieces of critical infrastructure—reality capture and 3D digital models are dynamic tools to help visualize facilities, monitor their health, and predict future performance. The result: better, more cost-effective maintenance that helps infrastructure last longer.